Fake Tintins

The morning my brother and I were leaving St. Malo to head back to England (one of the most depressing boat journeys in the world – leaving St. Malo and arriving in ugly Portsmouth), we happened across an antiques market opening up, not unlike the one featured at the start of The Secret of the Unicorn. Wandering through it, I glanced at a book stall unpacking its books. A book seemed to jump out at me: Tintin et les Blues Oranges, one of only two rare Tintin books I didn’t own (the other being the book of the film Tintin and the Golden Fleece). I picked it up immediately and almost put it down again after looking at the 16€ price tag: not only was it tatty but it was in French. But before I could put it back a voice boomed out: ‘dix’. Ten euros. I examined the book some more and said ‘cinq’. The man gave a typically French shrug and held up eight fingers. I held up seven and he said ‘okay’.

My brother mocked me afterwards, pointing out that the price went down from 16€ to 10€ in the time I’d merely picked up the book; he was obviously keen to get rid of it. I thought I’d gotten a bargain, however; it’s pretty hard to find. The live action films Tintin et les Blues Oranges (1964) and Tintin and the Golden Fleece (1961) were both released on DVD by the BFI last year, but their accompanying book versions have been out of print since the 1960s.

I still reread my complete set of 24 Tintin books. But with the last one being published in 1976 and Hergé dying in 1983, there hasn’t been a huge amount of new Tintin material since. There’s been loads of merchandise produced by Moulinsart, but it’s hardly essential, though I am guilty of owning some of it. No, the only real surprises in Tintin world since Hergé’s death has been the publication of Tintin and Alph Art, the final unfinished Tintin story, consisting of sketches and notes; and the English translation published a few years ago of the controversial Tintin in the Congo (first published 1931). Also interesting was Tintin and I, the 2003 documentary about Hergé; and books about Tintin including Tintin in the New World (A Romance) by Frederic Tuten (a friend of Hergé’s) in 1993, a novel with Tintin finally discovering women; and the academic, post modern Tintin and the Secret of Literature by Tom McCarthy (2007). Of course, there’s also been last year’s horrendous Spielberg film.

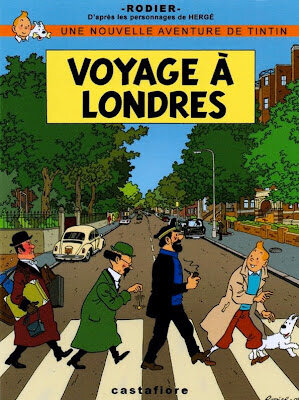

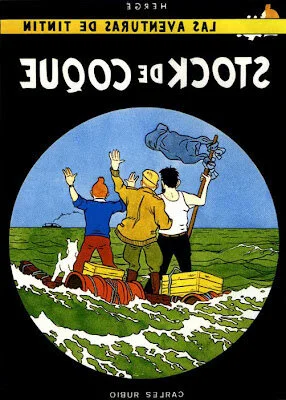

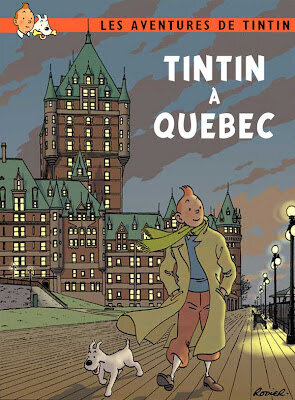

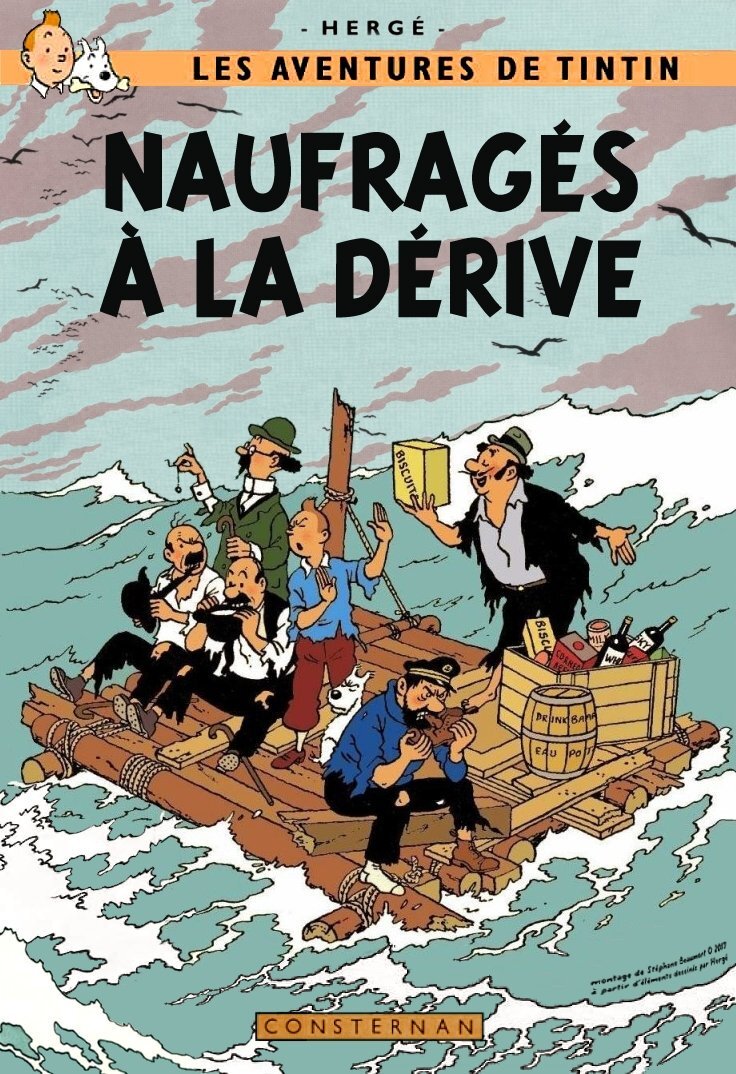

The main facet of Tintin which has been growing since Hergé’s death and rise of the internet is fake Tintins. Mostly these are just fake covers; sometimes they’re whole books (the most bizarre being Tintin au Congo a Poil; which is, er, Tintin in the Congo, nude). Fans are mixed about them; fakes are, strictly speaking, illegal, and a good percentage of them are sexual (Tom McCarthy identified three types of parody: the sexual, the political and the artistic), so they’re not really as Hergé would have envisaged them. However, a lot are drawn by true fans who are obviously passionate about Tintin. The best ones continue the legacy of Tintin and are a tribute to Hergé, showing great imagination and technique. Canadian Yves Rodier is one such artist producing Tintin parodies; he is perhaps most famous for unofficially completing Tintin and Alph-Art.

Tintin’s iconic look, his innocence and Hergé’s crisp, clear lines make him ripe for parody. Fakes seem to be all the world. I remember seeing Tintin T-shirts and posters in South-East Asia: Tintin in Vietnam, Thailand, Cambodia. He only had twenty-four adventures in the official books; the parodies let him keep on travelling.

Previously on Barnflakes

Hergé’s favourite Tintin panels

Lookalikes #10: Thomson and Thompson

Eponymous heroes ‘largely dull’

Tintin never went to Cambodia