The Strange Worlds of Gurney Slade and Midwich

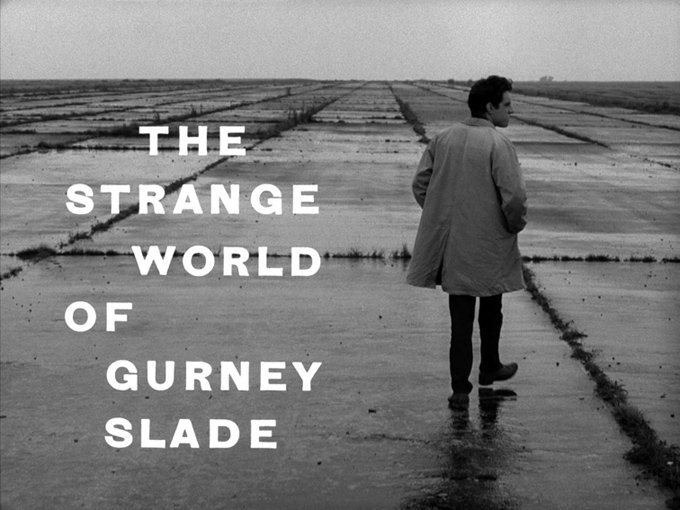

Gurney Slade: looking for love on a vast, empty, abandoned, overgrown and wet airfield.

The Strange World of Gurney Slade (1960 TV series)

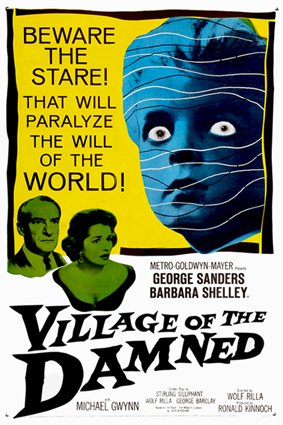

Village of the Damned (1960 film)

I love TV programmes or films that start off with something so unexpected, so out of the ordinary that it takes the rest of the series/film to explain it. Such is the case with The Strange World of Gurney Slade and Village of the Damned. I watched them within a few days of each other. They were made in the same year and are in black and white. Both are distinctly British yet present strange views of the nation.

The Strange World of Gurney Slade starts as off as a dull, stereotypical working class TV sitcom; a family have just moved into their new home. The wife ironing, the son doing his homework, neighbours popping round to introduce themselves. The husband, Gurney Slade (played by Anthony Newley) looks preoccupied and angry, and doesn’t say his lines on cue. The other actors, embarrassed and confused, try to cover for him. Then he gets up, puts on his raincoat, crushes some biscuits in a newspaper and storms off the set, to the exasperation of the floor manager (played by a young Geoffrey Palmer). Gurney leaves the studio, not saying a word, and skips along the street, free as a bird.

If nothing prepares the viewer for that opening (even now), nothing prepares them for the rest of the series either, six episodes of ramblings by Gurney Slade and surreal encounters with animals and dustbins. The series constantly breaks the fourth wall with Gurney’s ruminations on modern life directed to the camera. Shot on location with 35mm film, the series often looks as good as any movie and certainly better than most TV of the time. Scenes in the British countryside (including walking past a road sign for Gurney Slade, a village in Somerset where the series got its name) such as discussing carrying grand pianos with ants or singing a duet with a scarecrow have lovely cinematography.

Despite the surreal humour, there is a dark side to the series. Gurney himself, in the first episode, comes across as an unemployed actor (David Bowie’s ‘cracked actor’, who, incidentally, was a fan of the show) with possible mental health issues, as he talks to himself (and us) in a voice-over or has imaginary conversations with a stone, adverts, dogs and bins. Towards the end of the episode, he barges in on the family he left at the start, who are crowded around a TV watching a series about him (the same show we are watching). Talk about meta. At the end of the episode, Gurney complains about ‘Big Brother’ watching him constantly (Orwell’s 1984 had only been published a decade previous) and runs off, a paranoid actor with a vacuum cleaner telling everyone ‘leave me alone’.

Gurney’s paranoia is eventually justified as it’s revealed he isn’t the free spirit he imagines himself to be (all along he has had altercations with authority, from a policeman to a lawyer), but a pawn in the game of an anonymous TV controller pushing all the buttons; more specifically, and literally (in a rather disturbing ending) Gurney is a mere puppet.

There are constant references to the artificial nature of TV, of the relationship between actors and viewers. This comes to a head in the final episode when all the characters (not the actors) seen in previous episodes gather in the TV studio to complain that they now have nothing to do, and don’t know how to live outside the slim confines of the lives of the characters they played. They are eventually all assigned other roles, leaving Gurney on his own. As mentioned, Gurney turns into an actual puppet and is collected by the actor playing him, Anthony Newley. Heavy meta, man.

The catchy theme tune (which Gurney starts off each episode by miming a piano with his hand), the cool title fonts (which studio execs enquire what they are when they look around the studio in the last episode), Anthony Newley’s charm and the avant-garde flavour of the show, where you never know what’s going to happen next, make it very watchable. Maybe even more so to modern eyes.

I frequently found it very funny, with lots of classic one-liners – “There are lots of things more important than money. Trouble is, not everyone can afford them” – but episode four starts with Gurney on trial for not having a sense of humour. A foretaste of the public’s response, perhaps.

A failure on its initial release, the show is now said to be an influence on many shows, from Patrick McGoohan’s The Prisoner (1967) and the A Hard Day’s Night film (1964) to Monty Python (1969) and It’s Garry Shandling’s Show (1986). But also, why not, Alfie (1966) with Michael Caine, Peep Show (2003), late Seinfeld (1989), The Truman Show (1998) and a host of other post-modern films and TV shows. But nothing lives in isolation, and without The Goons (1951) or Hancock’s Half Hour (1954) they’d probably be no Gurney Slade.

Village of the Damned, directed by Wolf Rilla

Village of the Damned is based on the novel The Midwich Cuckoos (1957) by John Wyndham, arguably Britain’s most popular sci-fi writer. He was also responsible for The Day of the Triffids, The Kraken Wakes, The Chrysalids and Chocky, most of which were made into films or TV shows. If there’s a British sci-fi or horror film/TV show and it’s not by John Whydham, it’s probably nicked something from him (yes, I’m thinking of the opening of 28 Days Later).

Set in the fictional sleepy Midwich, Village of the Damned was filmed in Letchmore Heath, a village near Watford. The film begins with George Sanders, in his country pile, fainting mid-phone call. Then a driver slumped on his tractor going round and round, to shots of everyone in the whole village collapsed in what they were doing. Water overflowing in a sink, a record scratched and repeating, an iron burning a hole in a dress. It’s such an eerie sequence. A bus is late, so a policeman on his bike goes to investigate. He sees the bus, crashed into a ditch, gets off his bike and walks towards it. Falls unconscious.

The military moves in, putting a cordon around the village. A soldier wearing a gas mask, with a rope around him, gingerly approaches the collapsed policeman, and falls unconscious himself. A plane flies over the village, the pilot falls unconscious, the plane crashes. Absolute silence. Then a cow in a field wakes up, mooing. The humans follow, all waking up embarrassed as if from an illicit daytime nap. People in the village all appear unaffected until two months later, when every child-bearing woman in the village is found to be pregnant.

1960 was still a long way away from the swinging sixties; implying that wives had extra-marital sex was probably quite controversial (though Albert Finney was doing just that in Saturday Night, Sunday Morning, also 1960, but he was a man and it was up north). Husbands in the village are understandably suspicious and angry, especially if they hadn’t had sex with their wives for years. However, something is up when the pregnant women all have seven-month fetuses after five months, and all give birth on the same day to babies with piercing eyes, platinum blonde hair and demonic powers.

1960 was a decent year for horror films, with Psycho, Peeping Tom and Les Yeux Sans Visage all being released. Village of the Damned builds up tension and mystery superbly. Child actor Martin Stephens, who plays one of the evil children, also plays one of the possessed children in 1961’s The Innocents, another extremely creepy English horror film.

What Village of the Damned and The Strange World of Gurney Slade share is the unknown and unexpected happening at any time, even in sleepy English villages in 1960.

Previously on Barnflakes

Children of the 1970s

The Day of the Triffids book covers